Catering to the needs of digial-native Millennials and Gen Z, Mathew Joseph’s D2C brand has brought excitement back to the segment while taking care of the bottom line

Mathew Joseph, CEO & Co-Founder, Sleepyhead

Mathew Joseph, CEO & Co-Founder, Sleepyhead

Did these guys get up on the wrong side of the bed?” wondered Mathew Joseph. It was January 2017, and on one peppy morning in Bengaluru, the 32-year-old entered the office with a spring in his step. His excitement was understandable. The marketing director of Duroflex, the second-largest mattress brand in India with around 20 percent value market share, had to make a morning presentation to the board of directors explaining the pressing need to roll out an online-only mattress brand.

“What’s the need?” quizzed one of the members. “You already have an established brand,” he quipped, dampening the fiery spirit of the marketing honcho who was trying to nudge the over five-decade-old family business out of the comfort zone.

Pushed to the back foot, Joseph tried to foam up the argument. An online-only brand, he stressed, could cater to the needs and tastes of the digital-native millennials and Gen Z. The board, though, didn’t budge. The meeting stretched out over the next few hours. Not willing to back off, Joseph was ready to go to the mattresses. “I was trying hard to convince them,” recounts Joseph, who had earlier had stints with JPMorgan Chase and Tesco, and had completed a dual master’s in advertising and marketing from Leeds University Business School in England. “Duroflex was a very mature brand,” he reasoned. The online audience, he underlined, is very young and needed something they could relate to.

The task, though, was not going to be a sleep walk. Being one of the promoters of Duroflex—which was set up in 1963 by Joseph’s grandfather PC Mathew—was of little help. Reason: The young third-generation entrepreneur didn’t want to use the mother branding. “I didn’t have the Duroflex cushion,” recalls Joseph, who also didn’t want to use a ‘From the house of Duroflex’ branding on the products. “For the first three years,” underlined the co-founder and chief executive officer (CEO) of Sleepyhead, “the company will post around 5 percent negative Ebitda.” The loss talk triggered bedlam.

For the next few minutes, there was a deafening silence. “It was not minutes. They remained mum for a few hours,” recalls Joseph, adding that the marathon meeting went on for six hours. The 10-member board, which had been used to 10-11 percent positive Ebitda in Duroflex for years, was staring at potential losses. What exaggerated the odds for Sleepyhead was its business model. It was being positioned as a direct-to-consumer (D2C) brand. What this meant was that it would bypass the traditional retail footprint and channels of Duroflex, and would only be made available online. Though the idea and concept didn’t look too comforting, Joseph got backing on the basis of his stellar track record as marketing director of Duroflex. Sleepyhead got a seed capital of ₹70 lakh from the company, and Joseph was about to get what he didn’t hope for: Sleepless nights.

The first bout was not far away; it was lurking around the corner. Launched in October 2017, Sleepyhead clocked measly sales of three or four mattresses a month till December. Then came the move to put the mattresses on online marketplaces. The company, even by bullish estimates, had a stock for three months, which meant 30 mattresses. “But we got 150 orders,” says Joseph. “We were out of stock.” The lesson learnt was quick: The online space is unforgiving. After spending money to acquire a customer, he underlines, if one goes out of stock, it is a crime. The two-member team couldn’t handle a sudden rush of orders. Joseph was escalating calls to his colleague, who did the same in return. “You just can’t go out of stock,” he says.

But then excess stock is also a crime. Two months later, in early 2018, this was the next big learning for the fledgling CEO. This time, Joseph was well prepared to meet an unexpected surge in demand. So he stocked 200 mattresses. Then came the googly. He got only 100 orders. “Overstocking also is a crime because it hits the cash flow,” says Joseph. There were more teething troubles for the new brand. After rolling out a website, the startup had factored in that it needed server space sufficient for around 10,000 visitors. The website crashed. Reason: It got over 20,000 hits. With just two people in the team, Joseph’s dream was fast turning into a nightmare. It was the consumers’ turn to be on the wrong side of the bed. “In February 2018, we were on calls for six hours continuously to fix consumer orders,” he recalls.

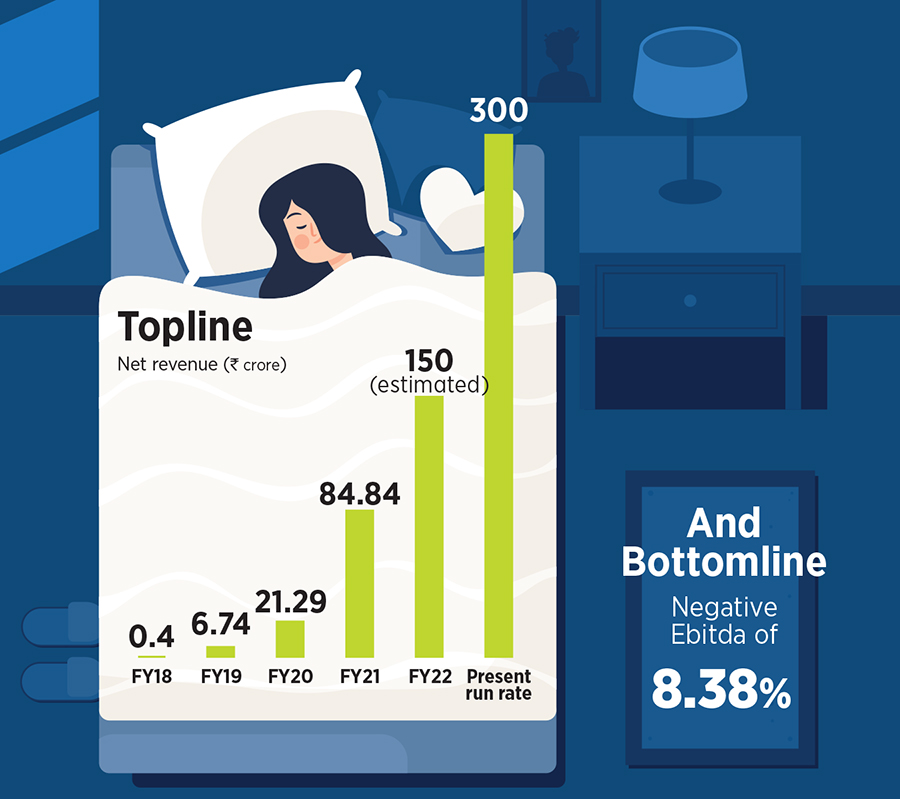

After a few months of hard lessons, the foam-based brand found its sweet spot and home. In FY18, it clocked a net revenue of ₹40 lakh; the next fiscal, the numbers jumped to ₹6.74 crore. In FY20, Sleepyhead posted sales of ₹21.29 crore, which pole-vaulted to ₹84.84 crore the following fiscal. For FY22, it is estimated to close at ₹150 crore, and is clocking a run rate of ₹300 crore. The company has raised ₹200 crore so far, and counts Lighthouse and Norwest Venture Partners among its backers.

After a few months of hard lessons, the foam-based brand found its sweet spot and home. In FY18, it clocked a net revenue of ₹40 lakh; the next fiscal, the numbers jumped to ₹6.74 crore. In FY20, Sleepyhead posted sales of ₹21.29 crore, which pole-vaulted to ₹84.84 crore the following fiscal. For FY22, it is estimated to close at ₹150 crore, and is clocking a run rate of ₹300 crore. The company has raised ₹200 crore so far, and counts Lighthouse and Norwest Venture Partners among its backers.

While the product portfolio includes mattresses, beds, sofas, sofabeds, recliners, and bedding accessories, it is planning to roll out bedsheets, cushion covers and furniture, and transform itself into a lifestyle home decor brand. Staying true to the DNA of a D2C brand, 25 percent of the sales come from its own site; 74 percent from marketplaces, and 1 percent from its offline experiential centres. “At Duroflex, I was in a comfort zone,” says Joseph. “I realised I needed to unbox.”

The unboxing started with boxing. Sleepyhead disrupted the market with its ‘bed-in-a-box’ concept, which meant rolling the mattress, putting it in a box and selling it to consumers. The new product, and strategy, were based on consumer insights. Joseph explains. The mattress category was quite boring in two aspects. First was the communication. While the big boys were doing a brilliant job in underlining the virtues of a good sleep, and various aspects of sleep, the message lacked punch.

The second boring aspect was the entire process of buying a mattress. From taking a crash course in understanding multiple kinds of mattresses to zeroing in on one of them, and then haggling with the shopkeeper to ensure that the consumer doesn’t pay for the transport was a big hassle. “The entire process was killing the happiness of buying a new mattress,” maintains Joseph.

The second boring aspect was the entire process of buying a mattress. From taking a crash course in understanding multiple kinds of mattresses to zeroing in on one of them, and then haggling with the shopkeeper to ensure that the consumer doesn’t pay for the transport was a big hassle. “The entire process was killing the happiness of buying a new mattress,” maintains Joseph.

The segment needed some excitement. Joseph pepped up the chutzpah quotient by compressing the foam mattress in a box, and taking it directly to the doorstep of a user. “The tagline of our first campaign was ‘unbox your comfort zone’,” he says smiling. While people were used to unboxing a smartphone, Joseph gave them a new experience of unboxing a mattress. Videos of a bunch of consumers were uploaded on YouTube, and those went viral. Sleepyhead started to grab eyeballs.

For Joseph, the next big unlearning was to stay lean in pricing, team and portfolio. For about 18 months, Sleepyhead continued to be a two-member team. The vibes got reflected in the product portfolio as well. While an offline brand would have rolled out 20-25 types of mattresses, Sleepyhead stayed frugal and came up with only three or four options. Extensive consumer surveys gave a sense of the kind of firmness and comfort that users were looking for in a mattress. The idea of a selective portfolio was to reduce the confusion for consumers. “Make it less confusing and the conversion rates would go high,” says Joseph.

One set of consumers, though, stayed baffled. “You kept asking for what consumers are looking for and added all those features in Sleepyhead,” was how the Duroflex retailers reacted. It was difficult for Joseph to make them understand why Duroflex and Sleepyhead should have an independent existence in all aspects—pricing, positioning and technology.

For Anshul Jain, taking a leap of faith made sense. The managing director at Lighthouse bought the box and the Sleepyhead story even before the product was officially rolled out. The reason was simple: The team. “When we invest, the most important thing is the team,” she says.

For Anshul Jain, taking a leap of faith made sense. The managing director at Lighthouse bought the box and the Sleepyhead story even before the product was officially rolled out. The reason was simple: The team. “When we invest, the most important thing is the team,” she says.

Though Duroflex was a legacy brand, the brothers running the show were open-minded, progressive and passionate. “That gave us a lot of confidence.” The icing on the cake was a differentiated product.

There was another differentiation, though. Joseph had ensured that Sleepyhead stayed lean in cash burn as well. Coming from a business family meant building and running the business in a traditional way. What this means is not letting the bottom line balloon. Joseph explains. If gross contribution after customer acquisition cost is positive, he points out, it means that one is building a sustainable business because the cost after that is primarily overheads and depreciation. “As long as I am running a brand with a gross contribution positive after my customer acquisition costs, I am okay,” he says.

Well, in a mattress business—or any venture—if one takes care of the bottom line, one doesn’t have to worry about sleepless nights.