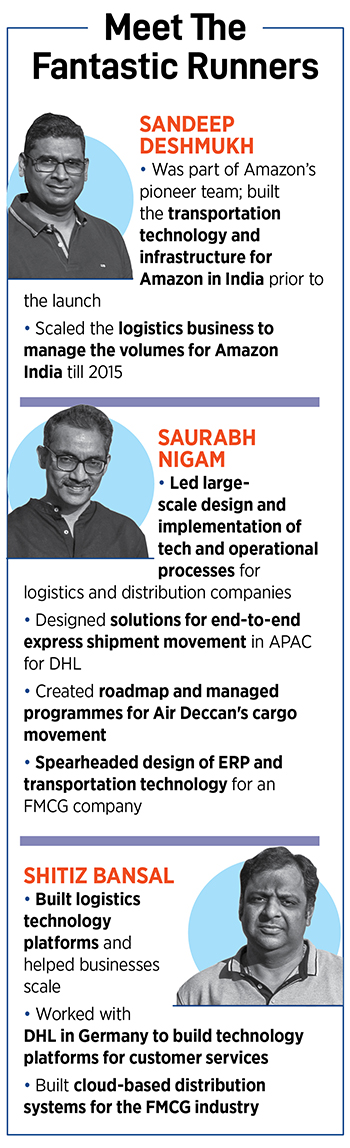

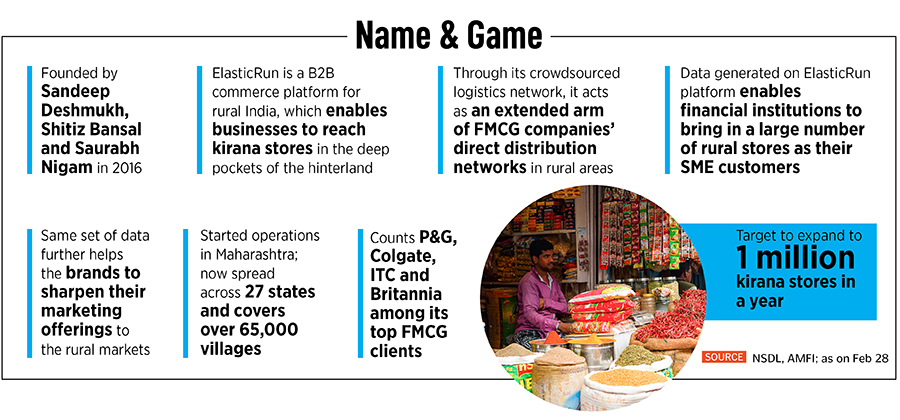

It was a very fuzzy idea,” recalls Sandeep Deshmukh. Among the first few employees of Amazon India, the software engineer was instrumental in building last-mile delivery for the American online retailer in India. During his five-year stint—just two months short of five years to be precise—Deshmukh spotted a massive cloud on the horizon. “There was no fulfilment ecosystem in India, especially deep across the hinterland,” he recalls. And whatever did exist was too rudimentary and primitive. “There was hardly any tech and digitisation,” he says, explaining how the last-mile delivery was almost missing. He, along with Shitiz Bansal and Saurabh Nigam, quit their jobs in 2016 and started ElasticRun.

The idea was simple. Deshmukh explains. ElasticRun would build a B2B commerce platform and create aggregated logistics network by using technology (read cloud), mobile and manpower available at local kirana and neighbourhood stores across the length and breadth of the country. “Availability on demand is the elasticity concept in the cloud world,” explains the software engineer, who was a key member of the engineering team for building the iCloud suite of applications (then MobileMe) for iPhone, iPad and the Mac OS during his stint with Apple from 2006 to 2010 at Cupertino, California. The preparation, too, was seamless. Having co-founders who had extensive work experience with logistics major DHL meant that ElasticRun had ticked all the boxes in terms of transport and technology. Customers, reasoned Deshmukh and the founding team, should not have to think about distribution fulfilment capacity they need in rural areas. It should be available to them on demand. “We were planning to bring the elasticity from cloud to the physical world,” he says.

The preparation, too, was seamless. Having co-founders who had extensive work experience with logistics major DHL meant that ElasticRun had ticked all the boxes in terms of transport and technology. Customers, reasoned Deshmukh and the founding team, should not have to think about distribution fulfilment capacity they need in rural areas. It should be available to them on demand. “We were planning to bring the elasticity from cloud to the physical world,” he says.

There was a small problem, though. Vani Kola spotted holes in Deshmukh’s virtual world built on the cloud. “She brushed aside our detailed business plan,” recounts Deshmukh, alluding to the pitch meeting with the top venture capitalist (VC). Such plans, the founder and managing director of Kalaari Capital underlined, usually go for a toss the moment the team hits the ground. “This is going to change at least 20 times,” Kola retorted. Deshmukh, though, was cocksure about his business plans. “It was a tough meeting,” he says. The silver lining in the dark cloud was Kola’s concluding remark. “I am sure you guys will figure out a way whenever it gets stuck.”

There was a small problem, though. Vani Kola spotted holes in Deshmukh’s virtual world built on the cloud. “She brushed aside our detailed business plan,” recounts Deshmukh, alluding to the pitch meeting with the top venture capitalist (VC). Such plans, the founder and managing director of Kalaari Capital underlined, usually go for a toss the moment the team hits the ground. “This is going to change at least 20 times,” Kola retorted. Deshmukh, though, was cocksure about his business plans. “It was a tough meeting,” he says. The silver lining in the dark cloud was Kola’s concluding remark. “I am sure you guys will figure out a way whenever it gets stuck.”

Things did get stuck after a few months. “She (Vani) was prophetic,” recalls Deshmukh. ElasticRun managed to get two big companies from the dairy and pharma sectors as its first clients, the team extensively worked on the accounts for a year, and the startup invested heavily in a bunch of pilot projects across the rural belts of Maharashtra. The companies too committed to try more innovative ideas and have a deeper skin in the game. Unfortunately, the promises remained on cloud, and nothing materialised. The projects never went live. “The first year was very tough,” says Deshmukh. The pharma and FMCG companies were either taking ages in deciding on the projects or didn’t have much appetite.

Things did get stuck after a few months. “She (Vani) was prophetic,” recalls Deshmukh. ElasticRun managed to get two big companies from the dairy and pharma sectors as its first clients, the team extensively worked on the accounts for a year, and the startup invested heavily in a bunch of pilot projects across the rural belts of Maharashtra. The companies too committed to try more innovative ideas and have a deeper skin in the game. Unfortunately, the promises remained on cloud, and nothing materialised. The projects never went live. “The first year was very tough,” says Deshmukh. The pharma and FMCG companies were either taking ages in deciding on the projects or didn’t have much appetite.

The initial journey was not easy. “Every day was a near-death experience,” says Deshmukh. The reason was simple. With little capital, the space to make mistakes too gets massively constricted. “One single mistake can kill you. So the psychological stress that you go through is tremendous,” he says. The conviction of building something massive in India, he underlines, is what kept the team energised.

The initial journey was not easy. “Every day was a near-death experience,” says Deshmukh. The reason was simple. With little capital, the space to make mistakes too gets massively constricted. “One single mistake can kill you. So the psychological stress that you go through is tremendous,” he says. The conviction of building something massive in India, he underlines, is what kept the team energised.

Though the efforts to rope in FMCG and pharma companies didn’t succeed in the first few years, ecommerce emerged as a saviour. The online retailers hired the services of ElasticRun to penetrate deeper into the hinterland. The rising aspirations and purchasing power of Bharat fuelled the growth.

Though the efforts to rope in FMCG and pharma companies didn’t succeed in the first few years, ecommerce emerged as a saviour. The online retailers hired the services of ElasticRun to penetrate deeper into the hinterland. The rising aspirations and purchasing power of Bharat fuelled the growth.

The startup started to gather pace on all counts. Operating revenue increased from Rs9.6 crore in FY17 to Rs63 crore the next fiscal, and Rs208.2 crore in FY19. The funding cycle gathered momentum. From a seed round of $2 million in April 2016 to a Series C round of $40 million in October 2019, ElasticRun managed to get marquee backers such as Kalaari Capital, Avataar Ventures and Prosus. Meanwhile, losses during the same period increased, but not at an alarming rate: Rs7.3 crore to Rs16.4 crore to Rs41.6 crore. Though the startup was clocking a healthy rate of growth, what was missing was a dream run.

It did happen in 2020 when the pandemic came knocking. The ecommerce rocket, which propelled ElasticRun so far, suddenly started to lose its firepower. “The first lockdown changed the game,” says Deshmukh. Two things happened simultaneously. First, all the traditional fulfilment networks collapsed. Second, while the first wave was spreading at an ominous pace in urban India, the rural counterpart was largely insulated. For the FMCG companies, which were now taking a massive hit in cities, the hinterland was the only saviour.

Suddenly, ElasticRun became a darling of the FMCG companies. From an operating revenue of Rs510.8 crore in FY20, the numbers leapfrogged to Rs1,087.1 crore in FY21. There has been no let-up in pace since then. While revenues jumped over three times in 12 months to Rs3,848.3 crore in FY22, ElasticRun entered the unicorn club when it raised its Series E round of $330 million and got new backers such as SoftBank and Goldman Sachs. The scale of operations too has expanded. Though it started from Maharashtra, ElasticRun is now spread across 27 states and covers over 65,000 villages; it counts P&G, Colgate, ITC and Britannia among its top FMCG clients, and has set a target to expand its network to 1 million kirana stores in a year.

The backers are excited with the pace of growth. “This is a unique company,” contends Rajesh Raju, managing director at Kalaari Capital. The VC fund invested in the startup at the seed stage. ElasticRun, he explains, is solving an India-specific problem through tech innovation. While people try to copy Western products and solutions, and try to replicate them in India, Raju underlines that Deshmukh and his team were building something very unique for India. Even though they have grown massively, they have always been practical about what they can deliver. “It’s one of the few companies that beats the numbers and business plans every single year,” he says.

The backers are excited with the pace of growth. “This is a unique company,” contends Rajesh Raju, managing director at Kalaari Capital. The VC fund invested in the startup at the seed stage. ElasticRun, he explains, is solving an India-specific problem through tech innovation. While people try to copy Western products and solutions, and try to replicate them in India, Raju underlines that Deshmukh and his team were building something very unique for India. Even though they have grown massively, they have always been practical about what they can deliver. “It’s one of the few companies that beats the numbers and business plans every single year,” he says.

For Ashutosh Sharma, head of investments (India) at Prosus Ventures, ElasticRun’s focus on logistics and rural distribution meant massive headroom for growth. “There are loads of inefficiencies in these sectors that can be solved in a scalable way only by use of technology,” he says. What has worked for the company, he points out, is building a crowdsourced, asset-light logistics platform that uses unutilised time, human resource and space in the network for doing ecommerce and FMCG delivery. The way they developed the network, he lets on, was very thoughtful, and had them well-placed to make the most of the opportunity in the long run. “The execution and the vision both convinced us to invest in ElasticRun,” he says. ElasticRun, Sharma reckons, is enabling huge transformation in rural India’s supply-chain ecosystem.

For Ashutosh Sharma, head of investments (India) at Prosus Ventures, ElasticRun’s focus on logistics and rural distribution meant massive headroom for growth. “There are loads of inefficiencies in these sectors that can be solved in a scalable way only by use of technology,” he says. What has worked for the company, he points out, is building a crowdsourced, asset-light logistics platform that uses unutilised time, human resource and space in the network for doing ecommerce and FMCG delivery. The way they developed the network, he lets on, was very thoughtful, and had them well-placed to make the most of the opportunity in the long run. “The execution and the vision both convinced us to invest in ElasticRun,” he says. ElasticRun, Sharma reckons, is enabling huge transformation in rural India’s supply-chain ecosystem.

For ElasticRun, which has grown at a heady pace, the going might get challenging. First, maintaining a furious pace of growth is not easy. With a revival of the growth story in urban India, companies might be tempted to focus more on high-value markets. The pandemic tailwinds too are not as strong as they were over the last few years. Second, the startup also has to keep a firm eye on losses. The numbers have jumped from Rs7.3 crore in FY17 to Rs92.1 crore in FY21, and might be even more for FY22. The company declined to share loss numbers for the fiscal.

For ElasticRun, which has grown at a heady pace, the going might get challenging. First, maintaining a furious pace of growth is not easy. With a revival of the growth story in urban India, companies might be tempted to focus more on high-value markets. The pandemic tailwinds too are not as strong as they were over the last few years. Second, the startup also has to keep a firm eye on losses. The numbers have jumped from Rs7.3 crore in FY17 to Rs92.1 crore in FY21, and might be even more for FY22. The company declined to share loss numbers for the fiscal.

Deshmukh, though, is not losing sleep. The company, he stresses, has grown almost four times last year, and 8x over the past two years. “We have delivered this while being extremely focussed on costs. That’s evident from the numbers,” he says. From FY20 to FY21, he underlines, ElasticRun grew more than 113 percent, but the losses increased only by 8 percent. It was possible, he reckons, because of thorough planning on the unit economics and execution to deliver the cost metrics. “Our unit economics is following the predicted trajectory,” he says, adding that going ahead, funding would only be required for expansion in the geographic coverage and the store network. “I think we have a real shot at building something 40-50 times larger than what we are today.”