On National Science Day, February 28, Biocon’s founder-chairperson Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw announced the biggest acquisition in her company’s history—to purchase the biosimilars unit of long-term partner Viatris in a deal valued at up to $3.335 billion.

Biocon shares promptly fell, losing as much as 17 percent over the next four days, to touch Rs328.2—the second-lowest price in the last 12 months—from the closing price of Rs394.55 the day before the announcement. The company’s market cap remains lower by more than 10 percent at close of Mumbai trading on April 13.

And, the fact that “in the recent times, pharmaceuticals stocks have corrected 15-35 percent from their highs as the valuations were stretched”, hasn’t helped either, points out Purvi Shah, DVP of fundamental research and pharma analyst at Mumbai’s Kotak Securities, which has a ‘Reduce’ rating on Biocon stock.

Investors worry that the large transaction, worth more than half of Biocon’s market value itself, is risky. The thus-far debt-free company has to borrow a lot of money for it as well. But Mazumdar-Shaw believes that this deal will be “truly transformational” for Biocon, making it a biosimilars powerhouse in a market currently dominated by large multinational companies.

The plan is to add Viatris’s biosimilars assets to Biocon’s IPO-bound subsidiary, Biocon Biologics, to make the Bengaluru-based biopharma company a global force in the biosimilars segment. And the deal is happening at a time when multiple original molecules are set to come off patent protection, allowing for the biosimilars segment to surge in the world’s biggest markets, the US, Europe and Japan.

This deal represents one of the two biggest inflection points in Biocon’s history, Mazumdar-Shaw says. The first was in 1998 when she bought out Unilever’s stake in Biocon India “to become truly independent and chart out our own future”. And now, with decades of preparation, investing in the scientific and engineering know-how, and the business operations of a large biopharma company, she is convinced that Biocon’s future will be decided by this deal.

Decadal global opportunity

“Biocon was among the early movers globally to pursue a high-risk high-reward strategy of developing biosimilars,” Shaw said when she announced the Viatris deal. The company had taken a strategic decision in the early 2000s to enter the niche area of biosimilars and biopharmaceuticals at a time when the regulatory pathway for biosimilars had hardly been defined, she added.

In fact, in 2007, Biocon sold its enzymes unit to Danish company Novozymes for $115 million, to focus on its biopharma business.

The biosimilars sector was marked by high entry barriers of complex science, rigorous product quality, stringent manufacturing standards and daunting regulatory challenges. Over the past two decades, Biocon invested in the science, advanced technology platforms and global-scale manufacturing to develop biosimilar biologics, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

The biosimilars sector was marked by high entry barriers of complex science, rigorous product quality, stringent manufacturing standards and daunting regulatory challenges. Over the past two decades, Biocon invested in the science, advanced technology platforms and global-scale manufacturing to develop biosimilar biologics, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

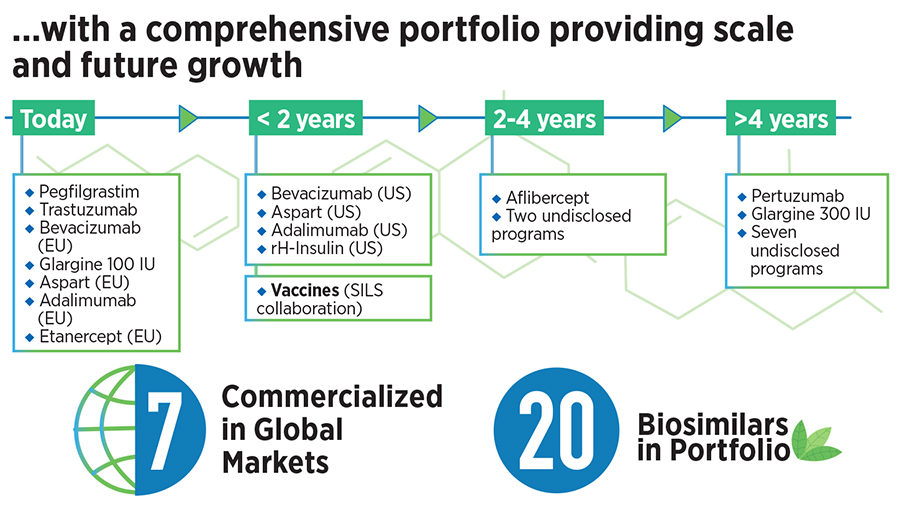

The idea was that there was an opportunity to raise Biocon’s revenue and profile by bringing biosimilars to markets around the world at more affordable prices. The effort has won global credibility, with seven molecules having been commercialised worldwide, touching 3.6 million patients on a yearly basis, and generating revenues of $384 million in the fiscal that ended March 31, 2021, she said.

And now, biosimilars offer a very attractive global opportunity, as a class of drugs that has emerged as an effective alternative to reduce the cost of novel biologic therapies. Over 1,000 biosimilars and follow-on biologics are under development for various therapy areas. Globally, the uptake of biosimilars has increased rapidly, she said.

About 65 percent of all biosimilars approved in the US have gained approval between 2018 and 2019, and 58 percent of biosimilars in Europe were approved between 2017 and 2019, according to an analysis by accounting firm EY, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

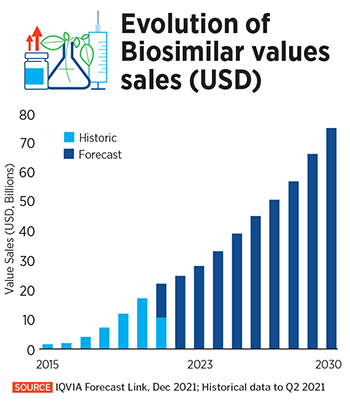

This trend looks to continue over the next decade, according to IQVIA, a US-based provider of health care industry advanced data analytics and insights. The global biosimilars market grew at a compounded annual rate of 78 percent between 2015 and 2020, reaching about $17.9 billion in 2020. It is expected to continue to grow 15 percent every year, between 2020 and 2030, reaching an estimated $75 billion within the next decade, IQVIA said in a January blogpost.

“In some countries, the biosimilars market is the dominant market now,” Duncan Emerton, executive director, custom intelligence and analytics, at Informa Pharma Intelligence, tells Forbes India. “Worldwide, there’s still some way to go, but the trend is such that we are seeing really strong uptake across lots of different products, indications and cancers, and I’m expecting that trend to continue to a point where the biosimilar is the dominant molecule.”

Fully integrated, independent

In this backdrop, the Viatris biosimilars acquisition sets Biocon Biologics up to become “a vertically integrated, world-leading biosimilars enterprise, both in terms of size and portfolio”, Mazumdar-Shaw said. The unit was established in 2019 when Biocon decided to consolidate the development, manufacturing and commercialisation operations of its biosimilars business under an independent entity. It will go public in the next two years, she said.

When Biocon first got into a biosimilars partnership with US-based Viatris (then Mylan) in 2009, it was for the co-development of a high-value portfolio of biosimilars for oncology and autoimmune diseases. The portfolio initially included three monoclonal antibodies—Trastuzumab, Bevacizumab and Adalimumab—and two recombinant proteins—Pegfilgrastim and Etanercept. This was one of the earliest partnerships in the global biosimilars space, according to the company.

The alliance also addressed the fact that Biocon did not have a front-end presence in the US market, Shah at Kotak says. With the US being a tougher market (than India), it’s not easy to have a front end and compete with the already-established companies. That’s where the tie-up came in.

In the past, “Biocon used to play it safe,” Shah says, and rely on these partnerships, avoiding the front-end marketing and operations. So it would usually have marketing tie-ups, and manufacturing would be its forte. But all the partnerships have not lasted, like, for example, one with Pfizer, which only lasted two years, between 2010 and 2012.

It was originally meant to be “a strategic global agreement for the worldwide commercialisation of Biocon’s biosimilar versions of Insulin and Insulin analog products: Recombinant Human Insulin, Glargine, Aspart and Lispro”, according to the company’s website.

Another factor that may have influenced Biocon’s decision to take the riskier step of this large acquisition could be that the few biosimilars products that it launched over the last two or three years have not garnered the kind of market share that it would have wanted, Shah says.

“So perhaps there was a bit of stagnation with those products’ market share in the range of 8-10 percent, and Biocon hasn’t been able to go beyond that,” she tells Forbes India. Therefore the thinking among Biocon and Biocon Biologics’ top executives may be that a more direct approach might yield better results, and Mazumdar-Shaw said as much in the press conference on February 28.

Her rationale is that the time has come to move from relying on the complementary capabilities of Viatris and Biocon Biologics to being much more tightly integrated as a standalone business that can move quickly when opportunities present themselves. Therefore controlling the operations end-to-end has become a necessity as the biosimilars market is poised to grow rapidly.

“By integrating Viatris’s portfolio, Biocon Biologics will have one of the broadest and deepest commercialised biosimilars portfolio,” she said. “This transaction will accelerate our direct commercialisation strategy for our current biosimilars portfolio. It will also make us future ready for the next wave of products.”

‘Huge amount of sense’

To begin with, right away, Viatris’s biosimilars revenues are estimated to be in excess of $1 billion next year, according to Mazumdar-Shaw. The deal gives Biocon full ownership of Viatris’s rights in biosimilar assets, including in-licensed assets, “enabling us to recognise combined revenues and profits”, she said.

This is a significant step up from the current arrangement where Biocon gets a smaller share of the economic benefits from its Viatris partnership, she said. In addition to the products mentioned earlier, Biocon Biologics also has the option of purchasing the rights to a biosimilar for the biologic Aflibercept, with a payment obligation by 2025. This asset is part of the deal and it has the potential to become a first-to-market product, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

This is a significant step up from the current arrangement where Biocon gets a smaller share of the economic benefits from its Viatris partnership, she said. In addition to the products mentioned earlier, Biocon Biologics also has the option of purchasing the rights to a biosimilar for the biologic Aflibercept, with a payment obligation by 2025. This asset is part of the deal and it has the potential to become a first-to-market product, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

The acquisition will also help Biocon fast track its efforts to position itself as a global brand, with a direct presence in the US, Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

“I think that the immediate thing that struck me was the size of the deal and it’s quite a significant investment for Biocon in terms of the dollars that it’s paying for Viatris’s biosimilars portfolio,” says Emerton at Pharma Intelligence.

“It’s very much aligned with a trend that we’re seeing within the biosimilars industry. And that is, in order for you to be able to effectively play in the biosimilars market, you’ve got to be a very big player,” he says.

Further, vertical integration and deep capabilities across the lifecycle of the products are crucial, he says. Very early on, several companies invested in developing biosimilars only to find out that it wasn’t as easy as they thought.

“It’s not the same as developing a (chemical) generic product.”

Biosimilars are called that because they are molecules derived from living cells that are similar to the original biologic molecules invented or innovated by their originators. They are also never exact copies, unlike chemical generics, but closely similar enough to be effective as the original biologic-based medicine.

The amount of money that the early movers were having to invest in pure development and manufacturing was quite significant, Emerton says. There was a fair amount attrition as a result, and a lot of companies just ceased to invest. They either sold their biosimilars portfolios to other companies or just simply terminated the development.

Gradually, there has been an emergence of the branded biosimilars company. “It was almost like if you have heritage in the biologics market and you were able to develop biosimilars at the same time, and you were able to position them as such within your wider portfolio, as solving a problem in relation to potentially access or choice or whatever it might be, then it was going to serve you well,” he says.

And in this game, “the bigger companies tend to survive longer”. Among them are Pfizer, Novartis and a handful of other companies such as SamsungBioepis and Celltrion. “They’ve captured the vast majority of the market in some of the really important classes of products, such as monoclonal antibodies,” he says.

Therefore the deal with Viatris is a move by Biocon to increase its standing within the market in terms of size, footprint, portfolio, choice, and in terms of being able to compete with the bigger companies.

“So on that basis, it made a huge amount of sense to me,” he says.

Execution risk

But investors worry that Biocon is funding the purchase—the biggest in the thus-far debt-free, cash-rich company’s history—through big loans. And further, success will depend on flawless execution of a plan to expand into the US market on the back of Viatris’s presence, in competition with some of the world’s biggest drug companies.

“So yes, there are a lot of questions in investors’ minds, and also because it (Biocon) doesn’t have a track record of taking up such a big acquisition, and execution risk now remains quite high. It’s a high-risk high-reward kind of a strategy at the moment,” says Shah of Kotak.

The exact final figures aren’t known yet, when it comes to how much Biocon needs to borrow. The transaction is a combination of $2 billion in cash, $1 billion in compulsorily convertible preference shares to the tune of at least 12.9 percent stake in Biocon Biologics, $160 million in deferred payments and $175 million for the option to acquire biosimilar Aflibercept—the last two by fiscal 2025.

Viatris will also have a representative on Biocon Biologics’ board of directors. Mazumdar-Shaw has said that Biocon has received equity infusion commitments of $800 million and debt promises of $1.8 billion. The eventual IPO of Biocon Biologics will also help in reducing this burden, Mazumdar-Shaw said.

At Kotak, Shah’s estimate is that the net-debt-to-Ebitda of Biocon Biologics will be 4x, after the Viatris deal, and that could inch up given that the deal is expected to close in the second half of fiscal year that ends on March 31, 2023.

The Pharma analyst expects the deal to be fully earnings-per-share accretive from the fiscal year beginning April 2023. In FY23, her estimate is of a boost to EPS (earnings per share) of about 4-5 percent from the Viatris biosimilars unit, and upwards of 10 percent from FY24.

“The risk here is execution. If it can deliver, then this wouldn’t be a worry,” she adds.